Last year, I was invited to speak at Sparks by Offbeat, a learning and development event about the future of learning.

When the organizing team contacted me, I was traveling and reconnecting with family and friends. And it was during those exchanges that I realized that everyone around me appeared to be at a crossroads in their personal and professional lives, uncertain about their next steps.

This observation connected a few things for me. It reminded me of the profoundly raw and exhausting nature of that very uncertain, "crossroad-y" or "limbo-ish" state. It reminded me of wayfinding and liminal spaces, two concepts I used more than once to explain that exact feeling of gliding or drifting when feeling lost.

Finally, it motivated me to structure this introspection into a brief presentation for the event, lightly explaining what that crossroad could be, why it hurts, and why it can prove itself valuable in the long run (as uncomfortable as it might feel in the short run).

So, just what is wayfinding?

In essence, wayfinding is about how we navigate physical spaces. However, it extends beyond the physical territory, reaching various other disciplines like graphic design, cognitive science, environmental psychology, and others.

Our knack for wayfinding has deep roots, dating back to our evolutionary history as Homo sapiens. In prehistoric times, it was essential to our survival as a species because it made it easier for people to share crucial information about resources and predators.

Today, even though our lifestyles are less nomadic, our innate wayfinding abilities continue to exist. Just as they help us navigate the physical world, these skills also prove invaluable for navigating the uncertainties we encounter in both our personal and professional journeys.

When we find ourselves in moments of doubt and ambiguity, these skills guide us, providing direction when we feel 'lost' in uncertainty.

From A to B

If we are so well-equipped, why is it still so difficult to get from point A to point B and solve whatever keeps us from moving ahead?

There are simply too many explanations, each with its own nuances and out-of-our-control circumstances. However, let us consider the idea of liminal spaces as one of the manifold reasons out there that might explain our own stuckness in our navigational quest.

What are liminal spaces?

Liminal spaces can often be seen in images of empty or abandoned places. They refer to areas or states in the midst of change, whether physical (like a corridor) or psychological (like adolescence).

The term "liminality" comes from the Latin "Limen," meaning threshold or moving from the known to the unknown. To put it another way, what we leave behind often feels more comfortable and familiar than what we see ahead.

Liminality in day-to-day (work) situations

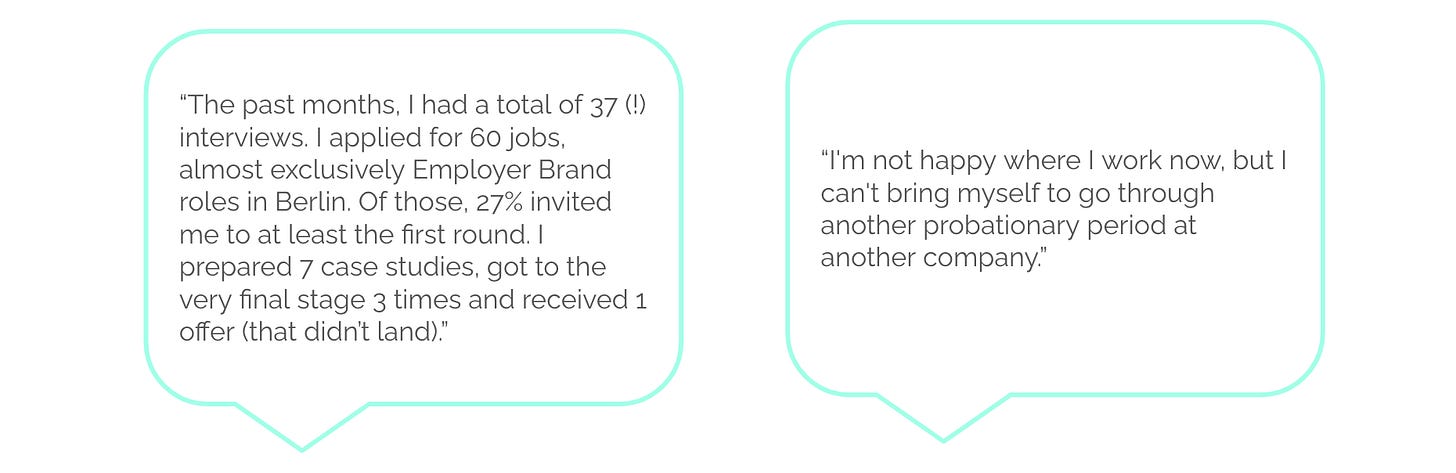

People enter liminal spaces (like the ones suggested below), either intentionally or involuntarily, when they find themselves temporarily "forced out" of their regular social roles and norms. They are neither here nor there, and they often experience a sense of disorientation, stuck in that A to B.

Some liminal spaces are more subtle than this, almost like meta-societal shifts that sneak into our lives in a dormant condition until they become more obvious that they exist but less evident about what they are.

Actionable wayfinding in liminal spaces

Without realizing it, those of us fortunate enough to have had easy and safe access to resources for personal development have already been engaging in constant, unconscious wayfinding. As a result, some of us have already developed systems to keep us on track with our personal and professional goals or to help us get back on track.

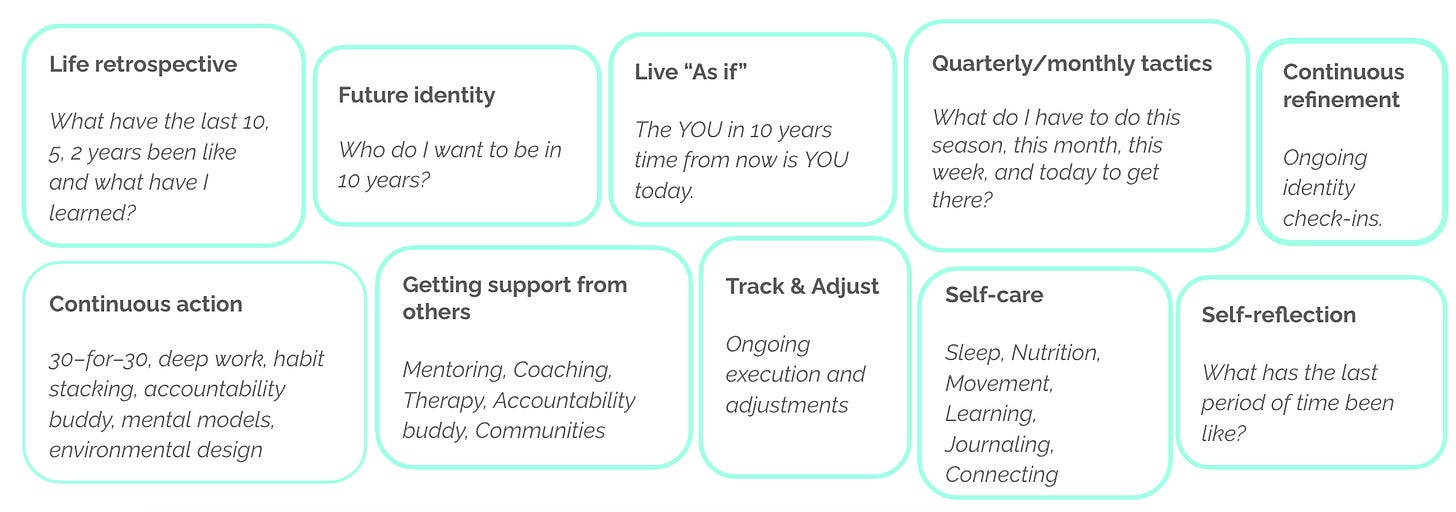

Take the example below. It's my very own flexible system that I developed over the years with the help of the books I've read, the people I've been following on social media, various branches of psychology, and a lot of common sense. In essence, it is a system that helps me challenge my own stuckness in that dreadful liminal space and find my way out. It involves self-assessment, future identity visualization, and action implementation.

And it works. Almost always. But not in the same way. But it works.

Honest & actionable wayfinding in liminal spaces

However, one thing that has always bothered me about those books, stories, and social media gurus is that they don't emphasize enough how wayfinding is never as linear and neat as illustrated above, and it's completely OK to "wayfind" your way as many times as you need, through and through.

Traditional strategies such as stacking habits, deep work, and self-reflection do not always work when you are pulled out of your daily work routine and let go, when you are dealing with burnout, mental health diagnoses, and pain because people are hurting each other all over the world.

But I'll say it again: messily experimenting with new routes and paths is totally OK. Taking a break from experimenting (or wayfinding) is also totally acceptable. Taking your time to adapt your wayfinding to your very specific circumstances and experience the beauty and ugliness of your own liminal spaces is perfectly fine.

Looking back on a few significant moments in my life when I felt lost, I realize that I frequently had to start again twice in the morning, three times in the afternoon, and at least once in the evening. To "wayfind" while feeling restless and trapped in an imagined corridor (sometimes of our own creation) is to override the life scripts we've taken for granted our entire lives. That's hard stuff.

So, how are we supposed to regain our sense of direction when we’re feeling lost?

Writing about wayfinding and liminality made me recall a scene from episode 5 of the Ashoka series. It doesn't matter if you haven't seen it or won't. It doesn't even matter if you like the Star Wars universe.

But just picture this: two characters, a droid and a Jedi, set out to find their missing friends. To navigate this journey, they must use unconventional means, like seeking help from giant space-whales with tentacles, creatures living neither on land nor at sea.

As they're about to jump into hyperspace, the droid notices that Ahsoka isn't sure where they're going and stresses that it could go anywhere. To this, Ahsoka replies confidently, ‘It's better than going nowhere.’

That’s pretty much the essence of all of those definitions, examples, and brief personal stories above:

Seeking to go somewhere or anywhere until it becomes a very specific direction is much better than staying in "nowhere."

To do that, we can use wayfinding, an innate ability, to navigate life's uncertainties, which are also liminal spaces or transitional zones marked by moving from the known to the unknown.

While regaining our sense of direction when lost is not an effortless feat, it is not impossible. We have the internal resources to conduct as many experiments as we want, at the pace that suits us best, until we get there.

And when we finally get there, we have the option of staying, continuing, slowing down, or taking a completely different path.